My family background is, admittedly, typically WASP. My maternal grandmother’s family is more aptly described as a clan (she had 8 siblings and eventually 19 nieces and nephews in addition to her own three children) rich with colonial ancestors, both New England Puritan and New Amsterdam Dutch. My maternal grandfather was a West Point graduate, a dashingly handsome cavalry officer and accomplished polo player. At the time my mother was born in the mid-thirties, her father was stationed in the Philippine Islands, but before World War II broke out the family returned to the United States. During the war years, my mother and her siblings lived in New York City and Garrison, NY, with her mother’s family, while my grandfather served with the OSS and, late in the war, in command of a combat battalion.

My father’s family also has deep roots, going back to Cape Cod in the 1640’s. Around the time of the American Revolution, his ancestors moved to Maine; my great-great-grandfather, known as “The Colonel” (we don’t know what he was Colonel of), moved to New York City not long after the Civil War. My great-grandfather, known as “Daddy Paine” or “Eagle Eyes,” established the Paine family’s long association with Willsboro, NY, when he took over management of a pulp mill there in 1885. My great-grandmother Maud died young, and Daddy Paine eventually remarried. His last child, a daughter and the only survivor of that generation, is two years older than my father and, at last count, a great-grandmother and a great-great-great-aunt. My father and his sister Molly grew up in New York City, where my grandfather worked as a stock broker.

I was born on the 8th of February, 1958, at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City, the first-born child of Hugh Jr. and Julia Paine. Perhaps I should say first-born human child—our mutt Mika was adopted from the ASPCA as a puppy while my mother was pregnant with me and feeling particularly maternal. Originally named Mike, closer examination discovered her correct gender; her name was duly modified by adding a vaguely feminine “-a” sound. About a year and a half after I was born, the family moved into an apartment at 1035 Park Avenue, which remained the family home until 1986. My father worked for his father as a partner in the brokerage firm Abbott, Proctor & Paine, while my mother filled the traditional homemaker role. I grew up in a wealthy environment, complete with a cook/cleaning lady: Catherine was something of a terror, although we loved her dearly, and I remember well her piercing Scots accent yelling “Billy!!” whenever I had neglected to keep my room sufficiently tidy. On the 6th of May, 1962, my brother Andrew was born, completing my nuclear family.

In due time, I went off to first grade at St. Bernard’s School on East 98th Street, where Dad had gone to school in the late 30’s and early 40’s. St. Bernard’s in those days was run very much on the British school model—Mr. Westgate, the Headmaster, was only the 2nd person to fill that position since the school was founded in 1904. I did not thrive there; in particular, I had a great deal of difficulty with compositions, which were required to be handwritten within specified “Comp Periods.” Today, perhaps, I would have been diagnosed with some form of mild dyslexia, ADD, ADHD or some other trendy acronym and treated accordingly, but in those days schooling was all about conformity.

By the 6th grade, it was apparent that I was failing along a broad front, so it was decided that St. Bernard’s and I would part ways. The following year, nominally my 7th grade year, I attended a relatively new “progressive” school where students were encouraged to devise their own schedules and course of study—remember, this was 1970-71 and very much still “the 60s” culturally. Although it was, in the end, a complete waste of time educationally, my year there gave me time to gain some much needed maturity. Also during that year, I joined the Knickerbocker Greys, a military drill organization for boys, which probably helped launch my interest in the military. In the fall of 1971, I went off to The Fessenden School, a “pre-prep” boarding school located in West Newton, MA. I thrived there, quickly establishing myself near the top of my class academically (although teenage laziness resulted in a slow slide from a high of 3rd in the class to barely in the top quartile by the time of my graduation the following year). That was good enough to get me accepted to St. Paul’s School in Concord, NH, were I arrived in fall of 1973 as a Third Former.

Meanwhile, beginning with an “eager beaver” two-week session in the summer of 1964, I spent every summer but one through 1973 attending summer camp at Camp Pok-O-Moonshine, in Willsboro. While I was far from being a strong hiker (I believe the word “whiny” has passed the lips of some of my ex-counselors), I still loved camp. I learned to shoot from the current director’s grandfather, Colonel H. T. Swan (known at camp as “The Colonel”), and gained an enduring appreciation for the majesty and beauty of the Adirondack region. In 1979, I returned as a counselor and, like many former campers and staff, continued to return year after year as a part-time volunteer during vacations from work or periods of unemployment. My brother Andrew’s attachment to Camp has been even stronger than mine; while he was working as a teacher, he had his summers available to work at Poko for the entire Camp season, and in time he became Head of Pioneer Section (boys age 7 to 9). After semi-retiring from active counselor work, Andrew continued as an Assistant Headmaster for many years.

Poko was convenient for my parents because the family summered nearby. Many of my great-grandfather’s children and grand-children bought property in the Willsboro area, much of it adjoining the original summer house on Flat Rock Point. The Camp, as such summer homes are often called in the Adirondacks, was the family hub in the summer, and there were always lots of cousins, many close to my age, staying nearby. Riding our bikes along the network of back-roads and dirt paths that criss-crossed the properties, we ran in a pack largely independent of adult supervision. Perhaps my closest friend growing up in Willsboro was my cousin Alice; we are only a month apart in age, and we were both possessed of highly active if somewhat bizarre imaginations.

More than any other place of learning, St. Paul’s School formed my character, and friends I made there have remained among my closest to this day. While challenging, prep school life in the mid-70’s was nowhere near as demanding as it is today. As students, we had plenty of free time, and the School’s campus was (and still is) surrounded by miles of woodlands and ponds which we happily explored on foot or, during the winters, cross-country skis. By my Sixth Form (high school senior) year, I was in tremendous physical shape from rowing (also known as crew). I rowed in the number 7 seat on the undefeated New England Champion 2nd Varsity Eight that year. (Each crew has 8 oarsmen, plus a coxswain to steer the boat. The SPS Crews raced inter-scholastically and were ranked 1st through 4th Boat. 1st and 2nd Boats were considered Varsity, 3rd and 4th Boats were Junior Varsity.) I was also among the pioneers of the school radio station, WSPS; Jon Panek, Tony O’Connor, Mitch Sklar and I established the first regularly scheduled broadcasts, which up until then had been quite sporadic. Finally, my other major extra-curricular activity was the Rifle Club, which I was President of for 6th Form year. Thinking back on the Rifle Club, I realize how very different the world is today: in 1976-77, as an 18/19 year old student, I was given keys to the rifle range, located in the basement of the gym, and had complete access to all the guns and ammunition stored there; the faculty advisor knew little about shooting, and only occasionally showed up at the range—I ran the range, serving as instructor and range safety officer. How times have changed! I doubt if the school ever replaced the rifle range when the new gym was built; indoor ranges today require expensive air filtration systems to avoid lead contamination (released into the air when bullets strike the back-plate) and chemicals discharged by cartridge propellant—never mind the Political Correctness of teaching teens how to shoot.

Although my grades were average at best, my very good SAT scores and English AP results were sufficient to get me accepted to Trinity College. I matriculated there in September of 1977, and graduated in May of 1981 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in English. Compared to my experiences at St. Paul’s, Trinity did not make a lasting impact on me. For the most part, crew and the college radio station, WRTC, were the primary foci of my college life, with academics a distant third place. I rowed on the Freshman and then JV Lightweight Crews (hard to imagine now—a lightweight crew had to average 160 lbs or less, with no individual oarsman over 165). I majored in English, primarily because the English Department had few required courses and no other graduation requirement, but I also took so many History courses that I was close to being a double-major, had Trinity allowed such things. The only reason I didn’t major in History is because the History Department not only had required courses but also a senior thesis and comprehensive exams as graduation requirements. That sounded too much like work to me at the time (why is youth wasted on the young?).

By the time my Senior year rolled around, I started to wonder what on earth I might be qualified for in terms of employment after college, and happened to stroll by the Career Development Office when some recruiters for the U.S. Navy’s officer programs were visiting. I’ve always liked ships and the sea, going back to trips on my grandfather’s 32-foot ChrisCraft on Lake Champlain, so I decided to apply. I was accepted, and a couple weeks after graduating from Trinity reported in at Officer Candidate School in Newport, RI. OCS was nothing like what was portrayed in the movie “Officer and a Gentleman”—that was modeled on the Aviation Officer Candidate School in Pensacola, FL—but the program was not easy. For the first week, known as Hell Week, new Officer Candidates were tightly regimented and taught the basics of military discipline. After that first week, however, discipline was relatively relaxed and the focus was shifted to the academic program, which essentially distilled all the Navy-specific classes that one might get at Annapolis or in Navy ROTC into a 16 week program. There were always two classes going through OCS at any one time, staggered two months apart, so half-way through our time there my class moved up to be Seniors and a new OCS class came in for their Hell Week (which we proceeded to inflict on the new Juniors with the same gusto as the previous Seniors had on us). At the beginning of October, 1981, my class graduated and I was commissioned an Ensign in the United States Navy. One of my proudest moments was when my maternal grandfather, a retired Army colonel, administered my oath of office.

After commissioning, I was given orders to USS Spruance (DD 963), the lead ship in a class of gas-turbine powered destroyers. Spruance was a fun ship to drive—she boasted four gas-turbine engines driving two controllable/reversible-pitch propellers, and could go from full power ahead (30+ knots) to dead in the water in less than two ship-lengths. I was appointed Electrical Officer and put in charge of “E” division in the engineering department, which meant I was responsible for the ship’s electrical and internal communications systems (my men were rated Electrician’s Mates (EM) or Interior Communicationsmen (IC)). The following spring, I reported back to Newport for Surface Warfare Officer School (Basic Course), a training program designed to give newly commissioned officers assigned to the surface fleet the fundamentals of division administration, ship-handling, tactics and shipboard engineering, among other subjects. Although I had expected to return to Spruance after SWO School, my orders were changed shortly before graduation, and I was sent to USS Moinester (FF 1097) instead.

Moinester was a very different ship from Spruance. A Knox-class frigate, she was smaller and less powerful, with a single screw propelled by two conventional D-type 1200psi boilers. These frigates, at the time, were the most numerous ships in the Navy—they were relatively cheap to build and operate and were thus attractive to budget-conscious military appropriators. Moinester wasn’t fast and had little to say for herself as an offensive weapon, but what she did have was an absolutely state-of-the-art anti-submarine warfare suite. Equipped with the latest TACTAS (tactical towed array surveillance) passive sonar system, including an advanced prototype model of the SQR-18A TACTAS hydrophone array, Moinester was capable of tracking submarines up to 50 miles away, depending on conditions, remaining out of sight and hearing of the target. When deployed, she also carried an SH-2F Sea Sprite anti-submarine helicopter, which could refine the target solution with sonobuoys and MAD (Magnetic Anomaly Detection) gear. In a hot-war scenario, the helo could also attack submarines using air-dropped torpedoes.

I spent the rest of my active duty career serving in Moinester, starting out as Auxiliary & Electrical Officer (A&E Division) in the engineering department, then transferring to the weapons department as Gunnery Officer (2nd Division). We made two deployments to the Mediterranean, in the summers of 1983 and 1985, both of which lasted about seven months; we also made numerous shorter cruises for training and operations throughout the North Atlantic and Caribbean. I made a number of good friends onboard, especially the infamous “Delta Squad,” which consisted of Tony Kurta, Bill Rozwood, Don Shirey and me.

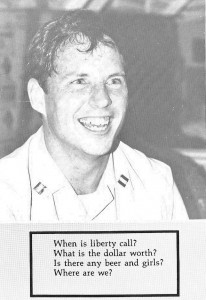

We got the label when all four of us were Ensigns during Moinester’s 1983 Med cruise, during a port-call to Malaga, a popular resort destination on the southern coast of Spain. The four of us had discovered a happy hunting ground for fun-seeking females on holiday at El Open Arms Pub, a Brit-run establishment in the nearby beach suburb of Torremolinos. Our last night there, the Captain had imposed “Cinderella liberty,” which meant a relatively early curfew, to make sure we were all bright-eyed and bushy-tailed as we got underway early the next morning. As fate would have it, that night Tony, Bill, Don and I hooked up with a foursome of comely nursing students on holiday from Ireland; one thing led to another, and the last of us didn’t roll back on-board until long after the curfew had expired. The XO (Executive Officer, 2nd in command of the ship) was less than amused. At that time, in lieu of formal disciplinary proceedings (which could have serious future consequences), enlisted sailors who misbehaved ashore could be administratively placed on what was known as the liberty risk program; there were three classifications: class alpha meant an early curfew, class bravo meant a curfew plus being accompanied by a “responsible” superior petty-officer at all time ashore, and class charlie prohibited all liberty except by special permission. Since the four of us were officers, the XO decided to invent class delta: no shore leave unless accompanied by our department head, the XO or the Captain. Thus was born the Delta Squad. As it happened, the ship spent so much time underway that deployment that by the time we got to our next port-call we’d been released from restrictions, but the nickname stuck. By the 1985 deployment, the four of us (now Lieutenants) shared a four-man stateroom located next to the Captain’s cabin just under the bridge. Originally intended as an embarked unit commander’s cabin, the stateroom had its own head (bathroom for you non-seagoing types) and shower, and was relatively luxurious. The XO always claimed, only half in jest, that he put us all there so the Captain could keep a closer eye on the Deltas.

My active duty commitment ended in October of 1985, shortly after the ship returned from my second Mediterranean deployment. I returned home to New York, and for a few years lived again with my parents, moving with them from Manhattan to Forest Hills in 1986. I had some rather inflated ideas on how marketable a former Navy officer was in the job market, so it was some time before I finally decided to lower my sights a bit and get whatever job I could. Being something of a computer enthusiast, I got a job selling computers at an office products company in Manhattan; a year later, a colleague in my Navy Reserve unit induced me to come work for his firm in White Plains, selling networked systems running a high-end business accounting software suite. Two years after that, a recruiter cold-called me looking for people with sales experience to work for Marine Midland Bank, and that’s how I ended up in the financial services industry.

In 1990, I joined Holland Lodge, a venerable and prestigious Masonic lodge founded in 1787, which two of my great-grandfathers, my grandfather, father and younger brother had been members of. My grandfather, father and brother had all been Masters of the Lodge (although Andrew didn’t become Master until after I joined). Freemasonry is a wonderful institution, although much maligned in certain quarters. You can read more about it at Holland Lodge’s web site, listed on my People & Places page, but a quick summary is that Freemasons are not devil-worshipers, anti-Christian, nor secretly running the world. Masonry is not a religion, although it requires a belief in deity for membership (which deity is left up to the individual’s conscience); in fact, Masonry encourages its members to live a life of faith and worship within the context of their own preexisting religious practices, be it Christian, Jewish, Muslim or otherwise. From this, one might get the idea that spirituality is fundamental to Masonry, and that is true to some extent. However, Lodges are also social clubs and charitable organizations, and these facets of Lodge life are just as important.

A year after being raised in Holland Lodge, I joined the line of officers as Junior Steward (although drop-outs in the line over the summer advanced me to Senior Steward by the beginning of the season proper). In Holland Lodge, there are a total of 11 “line” officers, plus two others (the Secretary and the Treasurer) who are usually elected to their posts as Past Masters. The top three, the Master, Senior and Junior Wardens, are elected by the membership, while the remaining 8 are appointed by the Master. In practice, one joins at the junior-most position and advances one “chair” each year, sometimes skipping over a position or two if somebody drops out of the line. I worked my way through the chairs, and was installed Worshipful Master for the 2000-2001 season.

In 2003, I left the corporate world of the financial services industry and started my own business, River Road Financial Management. Freelance financial administration is a relatively new field, although elements of the services offered have been around in several forms for a long time. Essentially, a financial administrator for individuals offers a combination of bookkeeping and household fiscal management, handling such tasks as paying bills, reconciling financial statements, handling various payroll and employer filing requirements, and the like. Typically, clients are of two kinds: elderly or incapacitated individuals for whom these tasks are unduly burdensome, and otherwise capable individuals who wish to delegate some or all of these tasks in order to free up their energies for other things.

In addition to my work with individual clients, I also work with non-profit organizations. Non-profit bookkeeping and financial administration have a complex set of needs that are unique, and very few people outside the non-profit world (and a distressingly low number within it) know how to handle them. This is especially problematic for smaller non-profits that don’t have the resources to hire a full-time professional comptroller—board members and organizers are focused on the organization’s mission and programs, understandably, but this focus can come at the expense of proper bookkeeping and financial administration. An unfortunate result, for many organizations, is that annual audits become drawn out and expensive as the outside auditor is forced to forensically re-create the books of the organization to match the reporting and filing requirements of federal and state authorities. Furthermore, without clear, realistic and understandable financial statements and budgets, organizations have trouble qualifying for foundation grants and other funding sources. In extreme cases, non-profit organizations can lose their tax-exempt status by inadvertently transgressing against an increasingly complex charities regulatory regime.

Around the same time as the founding of River Road Financial Management, I also began exploring my spirituality. Although I’ve always considered myself a spiritual person, I had lost a sense of what my relationship with God was all about, and felt that I had moved away from whatever path God had in mind for me. I had been raised as a Roman Catholic, but I felt a certain ambivalence about elements of the Roman church’s dogma and institutional organization. My father was an Episcopalian, however, and I had always had one foot in the door of that church; when I decided to return to an active church life, I chose to be received into the Episcopal Church as a parishioner of St. Luke’s Church in Forest Hills. My spiritual life has blossomed in the wake of that decision, with the help of spiritual guides like Clark Berge of the Society of St. Francis, Tom Reese of St. Luke’s Church, my good friend Ian Montgomery, and many others. I’ve also been greatly aided by spiritual retreats at both Holy Cross Monastery and Little Portion Friary.

In 2021, I joined the Franciscan Community of Compassion as a Novice, subsequently professing vows as a Brother in September of 2022. The FCC is a small Franciscan community in the Third Order Regular tradition, based in the Episcopal Diocese of Long Island. We welcome brothers and sisters both married and single, and live dispersed in our own homes. We continue to work our usual jobs, and although called to live a simple life, we do not give up our possessions or live communally.

The FCC meets three times a week via Zoom for evening prayer, and once a month we have a chapter continuing education Zoom call. Once a year, we have an in-person retreat, usually somewhere in the Diocese, that lasts for four or five days. And yes, at the time of these photos, I had long hair. The habits you see in these photos are our “formal” wear—for everyday wear, we dress in appropriate regular clothing, always keeping in mind simplicity and humility.